This story is part of Spectrum News’ initiative, “Street Level,” which explores Ohio through the history and culture of specific streets and the people who call them home. You can watch part one of Street Level: Euclid Avenue here.

Stroll down Euclid Avenue and it’s a kaleidoscope of brand new buildings, thriving businesses, tourists and opportunity. Located in the heart of University Circle, the area has acted as an incubator for growing institutions.

Established in 1957, The University Circle Development Fund — later University Circle, Inc. or UCI — aligned the Cleveland Clinic, Case Western Reserve University and more than 30 other medical, educational and cultural institutions in the area, brought together by the shared goal of expansion.

“We were founded to buy land for the strategic growth of our institutions. And I think we succeeded wildly in that regard,” says former UCI President Chris Ronayne, who left his position with UCI to run for Cuyahoga county executive.

Today, the organization is an economic powerhouse.

“We spend, between those institutions, billions of dollars a year, and those billions of dollars a year have a multiplier effect on the Cleveland economy,” explains Ronayne. He estimates that the 40 nonprofit institutions that make up UCI have created a combined 50,000 jobs.

Despite the economic benefits, however, some worry that the growth of UCI comes at a cost to surrounding communities. Eric Ambro has watched the changes from a unique vantage point — a quiet cobblestone deadend just one block away from the bustling Euclid Avenue.

“Hessler is old,” says Ambro. “It’s a century old. All the buildings are old. It’s not perfect. That’s its character. That’s its nature. That’s why we like it.”

Ambro has lived on Hessler Street for more than 50 years. When he first arrived, the tiny block was a haven for Cleveland’s counterculture scene.

Eric Ambro with friends in the 1960s (Eric Ambro)

“We never thought of ourselves as being part of the hippie culture. We were just sort of that way naturally,” he says.

In 1969, the surrounding neighborhood was rapidly changing, and development was looming just around the corner. Concerned about the changes, Ambro and other residents formed the Hessler Street Neighborhood Association to protect the historic homes. They celebrated the inauguration with a small block party.

“The music was just impromptu jam sessions on somebody’s porch,” Ambro says.

The community made it a tradition, and by 1975 the annual event helped motivate the designation of Hessler Street as the first official historic district in Cleveland. Over the years, the celebration grew.

“We had no trouble getting musicians. We actually had trouble, you know, telling some of them that they couldn’t play because we had too many,” says Ambo.

Crowds gather at the Hessler Street Fair (Eric Ambro)

The fair continued for 50 years, at its height attracting more than 20,000 visitors to the tiny road. Then, in 2019, the music stopped.

University Circle, Inc. proposed a residential development that would sit on the site of the Hessler Street Fair Museum and food court.

“UCI called the meeting, and the developers said, this is what we’re going to build on your street, whether you like it or not,” recalls Ambro.

In September 2021, the garage that once housed the Hessler Street Fair Museum was torn down to make room for the new construction. It was a loss to the Hessler community, especially Ambros, who curated the museum.

Residents hope the street’s landmark status will help prevent the construction from moving forward.

“I understand change is constant,” says Patrick Holland, president of the Hessler Street Neighborhood association, “but I think we also need to remember that change is not always for the best.”

“The history of this street,” Holland says, “is something worth fighting for.”

Just across Euclid Avenue, the attitudes and accents change.

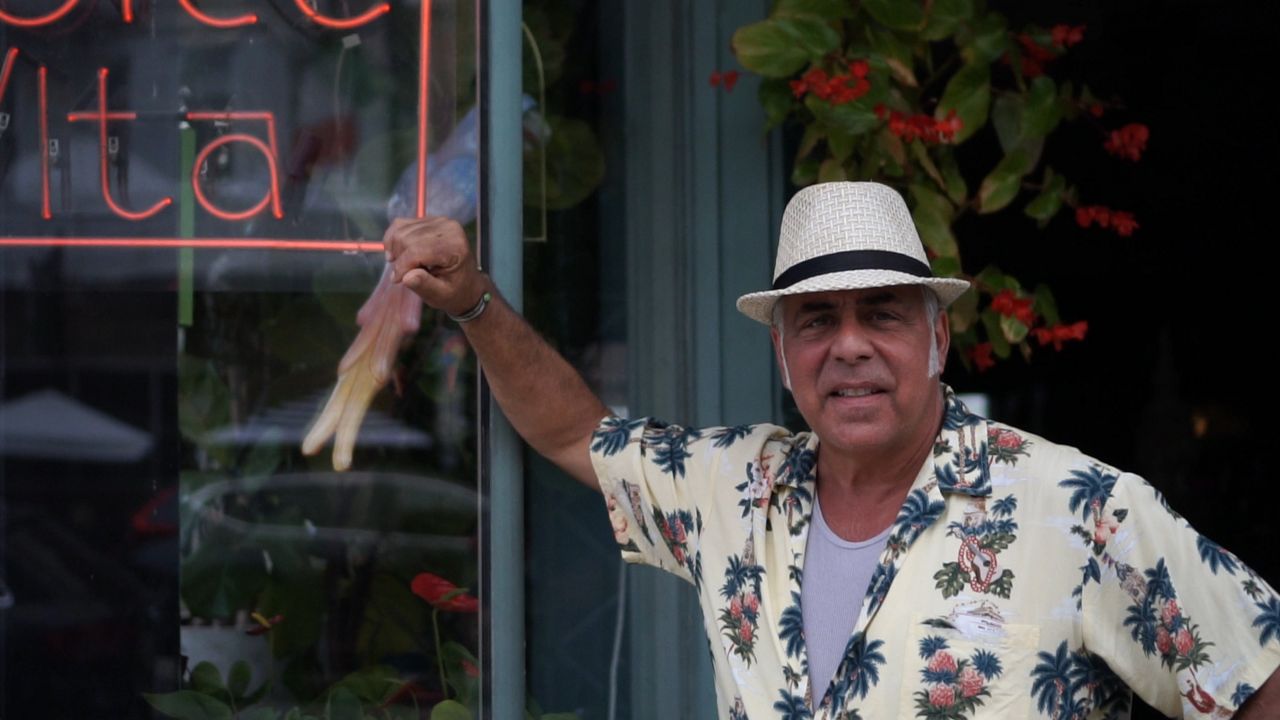

Terry Tarantino, a name and personality fit for a Scorsese film, is the long-time owner of Little Italy mainstay, La Dolce Vita.

Terry Tarantino stands in front of his restaurant La Dolce Vita (Spectrum News)

“This place is a bundle of fun and a bundle of craziness, and it is La Dolce Vita,” says Tarantino. “Yeah, it is the sweet life.”

The restaurant opened its doors in 1989. The location choice was strategic.

“The value in Little Italy was great and the proximity to Case and the other schools and University Circle being as attractive as it is,” explains Tarantino.

As University Circle grew, so did neighboring Little Italy. With the growth came more housing and a community-based arts and culture scene of its own — with art studios, galleries and a brand new museum, dedicated to Italian heritage.

Basil Russo, father of the award-winning directors the Russo Brothers, founded The Italian American Museum of Cleveland in the heart of Little Italy. The small storefront museum sits between two Italian restaurants on Mayfield; smells of freshly baked pastries and espresso fill the air.

“This is a very special, unique neighborhood with a lot of very wonderful history, and that story can’t be found at any of the large institutions or larger museums in Cleveland, but you can bet you can savor it and taste it and appreciate it in this museum,” says Russo.

Down the hill, past the shiny, state-of-the art medical centers on Euclid and 105th Street, Karamu House’s strong roots sustained them through the changing times.

“We talk about the national great treasures that we have — whether it’s the Cleveland Museum of Art or the Severance Hall and the Cleveland Orchestra — Karamu ranks with them.

When Tony Sias became President and CEO of Karamu House in 2015. The wealth of historic and cultural significance within the walls of the first African American theater in the country was palpable. Karamu House has been the touchpoint for Black Artists since before the Harlem renaissance.

Performer backstage at Karamu House (Cleveland Press Collection)

The theater is located in the heart of Fairfax, a community geographically within walking distance from University Circle but in terms of investment worlds apart.

“Although our historical trajectory has not been the same in terms of the same kind of investment, I feel like Karamu’s renaissance is putting us back on the right position center stage in arts and culture, not just only in Cleveland, but in the country,” says Sias.

Today, Karamu House is celebrating a surge in support, finishing up a massive renovation and welcoming visitors to the new space. Sias hopes the growth of nearby University Circle will spill over into Fairfax, and draw in new audiences.

“We’re optimistic about that impact of getting people to come and be a part of the Fairfax community,” says Sias. “Central to our mission is doing socially relevant theater. A part of our work is to, you know, celebrate the accomplishments of black folks, educate the community around the issues that are confronted, and then activate audiences around positive change.”

That message isn’t falling on deaf ears. It’s echoing in the marble halls of some of Cleveland’s most iconic institutions, sheltered in the heart of University Circle.

“The relationship that we have with our community is the most important thing possible. I mean, if you think about it, music without an audience doesn’t matter. It doesn’t exist,” says Severance Hall Chief Artistic and Operations Manager Mark Williams.

Severance Hall’s presence is enormous, not just structurally but culturally — reaching 160,000 people a year with their music.

“This is a living art and you know, we’re not museum pieces,” says Mark Williams. “We have to continue to be relevant and to serve the people who are living here today.”

That mission is reflected in the orchestra’s community outreach programs.

Williams acknowledges the importance of interacting with the community, not only as audience members, but as neighbors. “We start the conversation with what can we do to bring value to your community?” he says.

Cleveland Orchestra member Miho Hashizume tunes a student’s violin (Severance Hall, Home of the Cleveland Orchestra)

The orchestra works to take their music out of the building, organizing neighborhood engagement, free performances, and educational programs. Then, once a year, they bring the community to them, opening the stately doors of Severance Hall for a public celebration concert in honor of Martin Luther King — inviting an auditioned public choir to sing with them.

Using art to bridge the gap between artists and the community they serve, is a challenge that local artist Gary Williams is familiar with.

“There are so many people who live within walking distance of the art museum — never been there. Perhaps they didn’t feel welcome or invited. Maybe they just don’t know that it’s available,” he says.

Gary Williams and Co-Director Robin Robinson, run Sankofa fine arts in Glenville. One mural at a time, they are creating a path between those in the Glenville community and the world of art straight down 105th Street.

“Sankofa wants 105th Street, right now, to be that arts destination. And it’s a natural progression from the art museum, Karamu House, to the art museum, to 105th Street,” says Gary Williams.

It’s a process they believe the community should be involved in, every step of the way.

“We’ve gone door to door to actually talk to people and find out, ‘what do you think that it’s important for this mural to say to the community?” remembers Gary Williams.

The value of the mural project, he says, goes much deeper than a few coats of paint — it’s about the message that it sends to the people who live here.

Sankofa Fine Arts “Our Lives Matter” mural on 105th Street in Glenville (Spectrum News)

“What sticks out in my mind most is a young lady who came up and she had tears in her eyes and she said, you know, ‘this is so important that we understand that our lives do matter,” Gary Williams says, his eyes tearing up at the memory of the first mural they painted. “That touched me. That touched me.”