OHIO — The Ohio State Board of Education is facing new criticism for what the Campaign for African American Achievement and the Ohio NAACP said is a failure to treat Black and white students equally when it comes to academic expectations.

It was the first meeting of the year for the Ohio State Board of Education. They’re already getting some heat from the Ohio NAACP and Jimma McWilson, the director of the Campaign for African American Achievement, when it comes to closing the achievement gap on state report cards.

“They’re not in compliance with the decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Period. End of story,” McWilson said.

He said the proficiency level for “all” students needed to reach in the state used to be 77% for English/English Language Arts, but then things changed when the state had to create a 10-year plan as a part of the Every Student Succeeds Act.

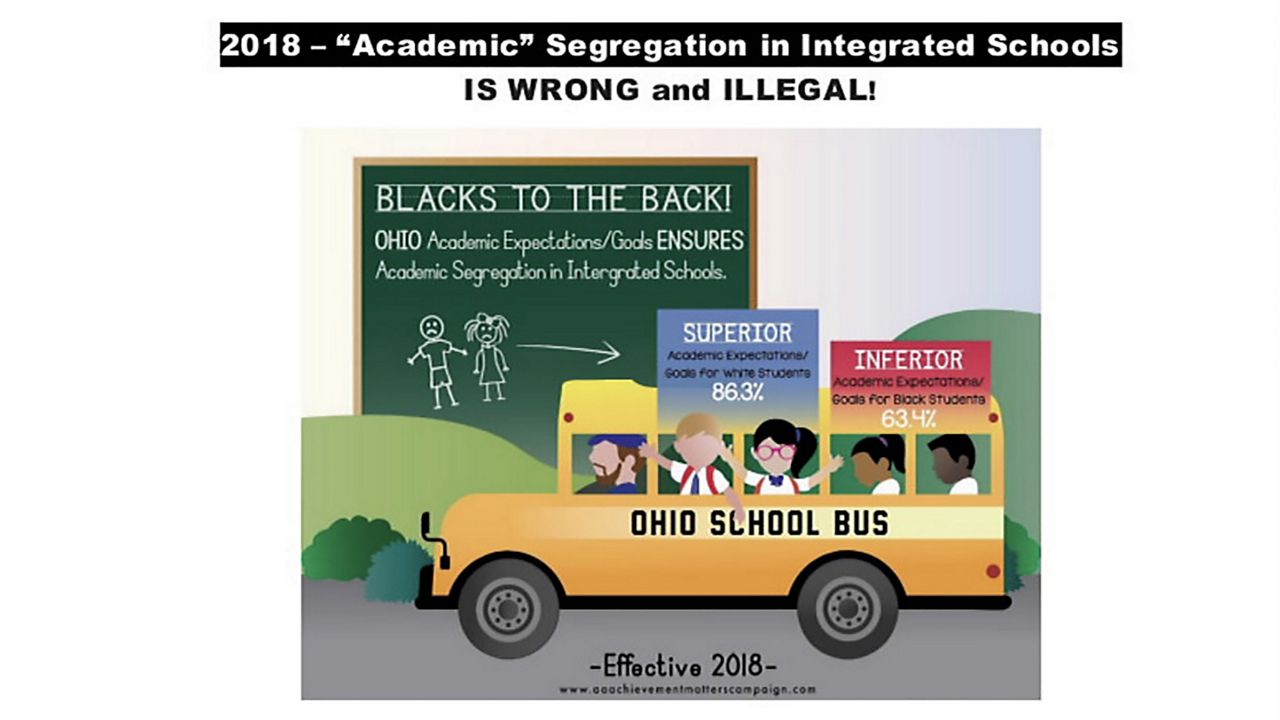

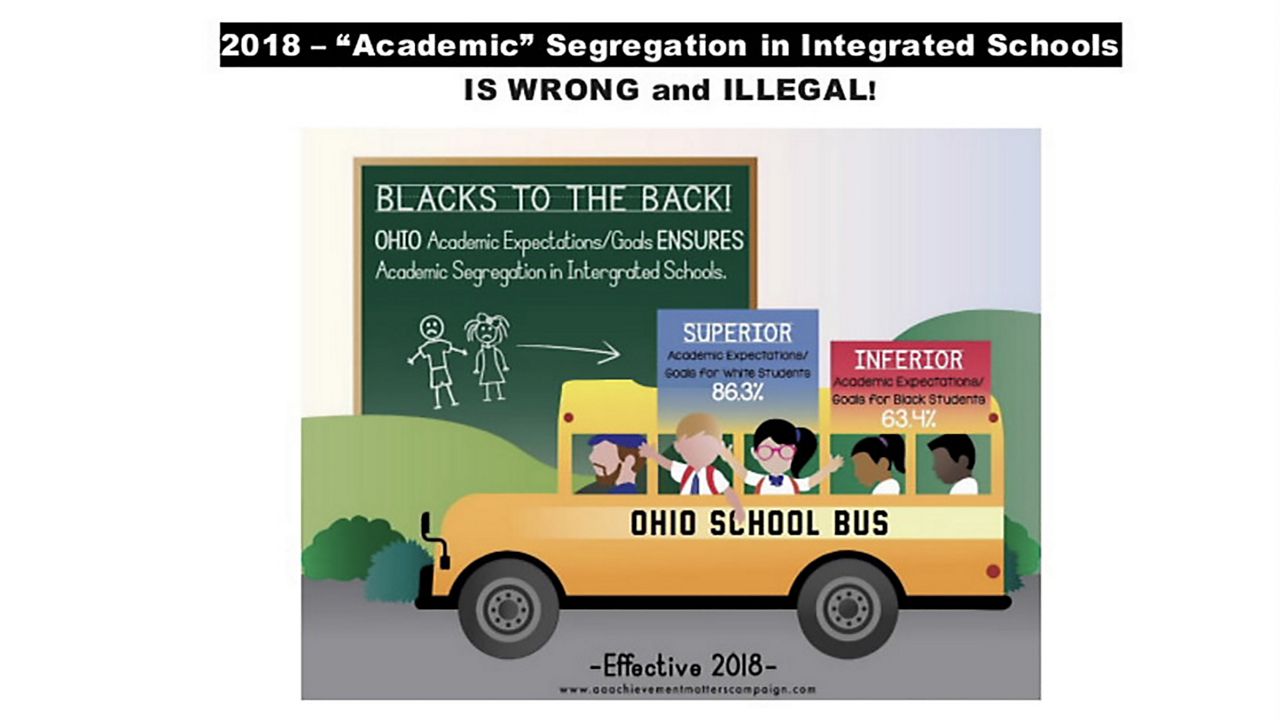

“All of the sudden in 2018. They gave Black people Black children. We have these academic expectations and goals for you, 63.4. And we’re doing you a favor because you were behind already so we’re giving you a little hand, but white kids will start at 86.3.”

So, McWilson explained the expectations were lowered for Black students and raised for White students.

“In other words, they created a Black track (and) a white track. Now, the reason why I use Black and white is because it was Black and white, in 1954. OK, that’s critical. But every other racial group is higher than the Black groups within that context.”

McWilson calls it inferior and superior academic expectations and goals — something he said is grounded in white supremacy.

“So, you’re still designing a plan — not to correct the problem, but to ensure that you’re still in your place when we finish our 10-year plan. The theme is academic segregation in integrated schools is wrong, and it is illegal.”

State Superintendent Paolo DeMaria said there’s confusion about what was done and what’s listed in the department’s 10-year plan for the Every Student Succeeds Act are not “expectations,” but “proficiency” benchmarks that were approved by the U.S. Department of Education, its civil rights division and the National Urban League.

“It is articulated equally without bias as to the type of student, because that is the is the goal,” DeMaria said.

Both McWilson and DeMaria agree there’s a problem, but wherein it lies is an issue.

“The state education system must perform and improve better visa vie underserved students than it would for other students, and so it actually prioritizes improving outcomes for Black students, for Hispanic students for students with disabilities for economically disadvantaged students,” DeMaria said.

For McWilson though, he said, “You have to do equitable things to get to equality.” And those benchmarks don’t allow the state to reach that point. Instead, he said, it gives educators an open door to do the bare minimum when it comes to educating Black kids.

“Well, if the state says that you really only have to be at this year, you only have to be at 65, but they don’t have to do all that work. And they will still be in compliance with the state,” McWilson said.

Ultimately, McWilson and the NAACP want the State Board of Education to understand their 10-year plan can’t simply be about making improvements, but it has to correct to a much bigger problem: The lack of equality. It’s something the Brown v. Board of Education decision already addressed.

“If you’re gonna have an expectation for the 1.7 million children in the state, you know, the state has a cutoff that cut off is a ‘C’, then you have it for all the children,” McWilson said.

McWilson and the NAACP hope to meet with the superintendent soon to resolve the issue and plan to come back to the board in February for more discussion. Right now, McWilson said they want the board to change the language in the 10-year plan to make sure all kids have the same academic expectations.